The Muslims were a force to be reckoned with for centuries in Spain, being a culture full of astronomers, artists, alchemists, doctors and farmers. Their only visible traces nowadays is the intricate architecture, crumbling castles and loud colourful fiestas to ‘celebrate’ their bloodthirsty farewell. But in their heyday “Al-Ándalus” had a substantial impact on Spanish society.

Entering Spain via Ceuta, which had been handed over to the Iberian peninsula in 710 AD, the Islamic invasion began in the south and south-east of the country and met with relatively little resistance, given that many aristocrats were able to keep their properties and income and even some of their power, particularly as the new settlers lived off taxes imposed on the population as a whole.

The original Christian inhabitants of what used to be Hispania had more or less resigned themselves to their land now being in the hands of this alien race, who in fact were far from a peaceful bunch – over the following 40 or 50 years, they brought in numerous Arab, Syrian and Berber immigrants and there were a good deal of punch-ups between them.

Generally, the Arabs, although fewer in number than the Berbers ( natives of North Africa) were the upper-class citizens, owning the most fertile land, occupying senior positions in the government and occupying the more luxurious, large properties. They looked down at the Berbers, considering them a common, uneducated race whose only useful purpose was to fight in wars. In practice, though, the Berbers were pissed off with the Arabs’ snobbish attitude towards them and so gave vent to their combative streak against their stuck-up fellow invaders.

Despite their superiority complex, the Arabs were not averse to marrying and having children with local females. Back then, a typical Spaniard was blonde with blue eyes and, over the generations, as the Arab bloodlines became heavily diluted with European genes, few of the aristocratic heirs of Al-Ándalus had the trademark dark hair and eyes and olive complexion associated with the Middle East.

Al-Ándalus, as the Islamic invaders were known, quickly got their feet under the table and established political independence, a monarchy and armed forces with fixed salaries for the inmates.

King Alfonso II was less pleased about these strangers entering his country and throwing their weight about, and launched a strong attack from Asturias in the north, but eventually they were forced to admit defeat.

However, even the disgruntled Alfonso II had to recognise that Al-Ándalus had improved social and economic conditions population of Spain on the 9th century, and although these were turbulent times as the people became hot under the collar about the push for conversion to Islam and the ‘arabisation’ of their culture, the invaders brought a great deal of useful knowledge with them, including medical science, art, architecture and farming methods, such as irrigation systems.

So, as time went on, the natives of Hispania began to realise that if they continued to follow their Christian faith, their taxes were higher, so converting to Islam became attractive as a form of tax evasion and, naturally, spread rapidly.

Despite everything, the Christians and Muslims generally got along very well. The former could practise their religion freely, as long as they paid their taxes and did not insult the Prophet Mohammed, and led a more or less similar lifestyle with no particular oppression or restriction.

The Christian kings in the north continued to simmer inside about the Muslims having made themselves at home without invitation, and often attempted to beat them down, particularly in the early part of the 10th century, an era that saw a surfeit of battles and bloodshed.

Yet the native Spaniards further south actually joined their new neighbours in fighting against the northern monarchs but the Muslims were unable to gain more territory in the north and so never established a stable central government.

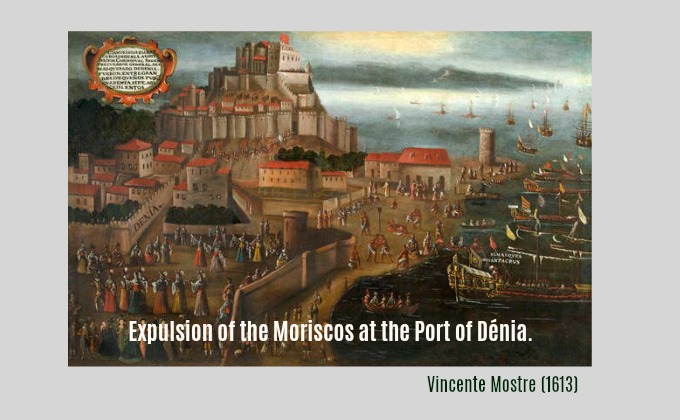

In the 11th Century, Moorish Spain was captured by the Almoravids, who were supplanted in 1174 by the Almohads. During this period, Christian rulers continued efforts in Northern Spain to recapture the south. In 1085 Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile recaptured Toledo. Cordoba fell in 1236, and one by one the Moorish strongholds surrendered. The last Moorish city, Granada, was captured by Fernidad V and Isabella I in 1492. Most of the Moors were driven from Spain, but two groups, the Mudejares and Moriscos, remained.

Seven hundred years of Moorish influence left an unmistakable mark on Spain, making it markedly different even today from the rest of Western Europe. The Moors not only brought their religion, but also their music, their art, their view of life, and their architecture…two of the greatest examples of which are the Alhambra in Granada and the Escorial in Cordoba.

Plus, of course, without all that history, the Spanish summer festivals, re-enacting their many bloody battles, would not exist! But knowing the Spanish folk, they would have found another excuse to dress up and party!!!!!